Killing Le Corbusier’s Beloved Parking Spaces

With the possible exception of Frank Lloyd Wright, there is no architect more famous than Charles-Édouard Jeanneret-Gris, far better known as Le Corbusier. While rightfully lauded for his massive contribution to what we now know as “modern” architecture and design, one of his other legacies is something far less awesome. The “Ville Contemporaine,” or “contemporary city” for the non-francophonic, was a master urban plan that represented his vision for the city of the future. VC centered around the “tower in a park,” hulking, X-shaped towers that acted as residences, offices and elaborate transit hubs. These spread-out, ultra-high density towers would get rid of the tight, hard-to-drive-through streets lined with sidewalks and two-to-six story, medium-density architecture that had dominated urban landscapes for the previous 1000 years or so. These towers would leave wide corridors for nature and, importantly, highways. You see, Corby was a car nut. He said this about the future of urban planning (a description that sounds suspiciously like a suburb):

The cities will be part of the country; I shall live 30 miles from my office in one direction, under a pine tree; my secretary will live 30 miles away from it too, in the opposite direction, under another pine tree. We shall both have our own car. We shall use up trees, wear out road surfaces and gears, consume oil and gasoline. All of which will necessitate a great deal of work… enough for all.

While the grand vision of the Ville Contemporaine never came to pass, the idea did get some traction, particularly with a guy named Robert Moses. Moses, probably the most influential force in 20th Century urban planning, loved the tower in a park and its car-friendly character.

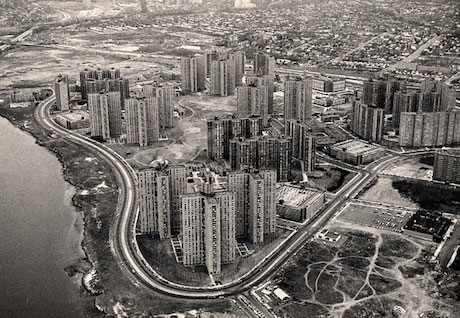

During his multi-decade reign as New York “master builder,” Moses sought to make New York City into a car centric paradise. Besides being responsible for the construction of countless bridges, tunnels, parkways and highways, Moses took on housing. In particular, he set about erecting public housing that fit more with the Corbusierian model. Over several decades following WWII, he destroyed countless gridded streets lined with row houses. In their stead, he put up large towers in parks. The building’s had the same cruciform shape as Le Corbusier’s VC models (pictured below are Le Corbusier’s unrealized model for Paris and a realized Moses public housing development).

There’s a healthy consensus that Moses destroyed countless vital neighborhoods. By replacing the doorstep, sidewalk and street-level small business with anonymous lobbies, hallways, elevators and meandering outdoor walkways, the towers served to effectively kill street life. Mosesian public housing often became vice-ridden community killers.

There’s a healthy consensus that Moses destroyed countless vital neighborhoods. By replacing the doorstep, sidewalk and street-level small business with anonymous lobbies, hallways, elevators and meandering outdoor walkways, the towers served to effectively kill street life. Mosesian public housing often became vice-ridden community killers.

People finally came around to seeing the virtues of walkable, human scale neighborhoods–a view promulgated most notably by Jane Jacobs–but the towers very much still remain, mostly along Manhattan’s outer edges and throughout the Bronx. The odds of resurrecting the old streets and neighborhoods are, we suspect, pretty low, and some of the towers are even thriving as naturally occurring retirement communities (NORCs).

But just because the towers remain, doesn’t mean they can’t be improved upon. More specifically, the towers, in line with the Corbusier/Moses car-centric ideal, include a ton of parking, much of which is underutilized. Moreover, their land-gobbling nature take up much needed land for housing and community spaces. Now a group of urban planners and architects are looking at those spaces and asking what else can be done with them.

A design team called “9×18” (referring to the dimensions of a regulation-size city parking spot) has created some ideas that rethink the parking mandated for affordable housing–many of these mandates are vestiges from the car-loving days of Robert Moses.

More about the project from Architizer:

Taking a particular East Harlem neighborhood as a case study, fellows Nathan Rich, Miriam Peterson, and Sagi Golan, supported by the Institute for Public Architecture, generated a set of recommendations and interventions for the city’s current surface-level lots and the policy surrounding them.

Some of those recommendations include fairly earthbound ideas like relating parking spots to distance from public transit–i.e. the further from public transit, the more spaces and vice versa. Others are a bit more unconventional, such as putting shared housing, workspaces and other amenities where the parking spaces once resided.

The project is like many we’ve seen recently like Casa Futebol, Stephan Malka and WeLive that seek to take existing structures–ones that are either un-or-under-utilized–and through incorporating architectural interventions, allow them to address the needs of their cities. These creative exercises–some of which will see the light of day, others will simply inform discourse about urban planning and architecture–show that a lot can be done to right architectural wrongs.

Find out more about “9×18” Project on Architizer and on the Institute for Public Architecture’s website.