In Praise of the Mobile Home Park (Don’t Call it a You Know What)

A recent NY Times article centered around Montauk Shores, a mobile home park on the far east end of Long Island, NY. Whereas many mobile home parks are paragons of low-cost living, Montauk Shores, with its prime location in the Hamptons, on a bluff overlooking the Atlantic, has 2K sq ft trailer lots fetching as much as $1.1M. These kind of sums are not unprecedented for mobile home lots. Paradise Cove in Malibu is a celebrity-studded mobile home park where homes and their lots frequently sell for north of a million dollars.

These stereotype-defying sums for sheet-metal-sided mobile homes seem to evidence the adage “location, location, location.” But there might be something more to the charms to mobile home park living than proximity to the beach. In every account of Montauk Shores and Paradise Cove, there is talk about community. The Times says of Montauk Shores, “Everybody knows everybody through barbecues and drinks on the decks, the children roam the dunes and ride bikes unsupervised, and the beach is a few steps away.” At Paradise Cove, Director Tom Shadyac reports that it takes 20 minutes to take his trash out because he’s always chatting with neighbors. The reason for these tight communities may be more than idyllic settings (though that is surely one reason). The tight community connections may be related to the tight-knit, human-friendly zoning mobile home parks enjoy.

In many ways, mobile home park zoning and architecture gets right what conventional zoning and architecture does not. Rather than separating people like traditional suburban zoning does, mobile homes bring people together. Rather than having arbitrary minimum building sizes like many suburban homes, mobile homes allow for compact–not tiny–and efficient architecture.

We were tipped off recently to a story by Charlie Gardner in the Old Urbanist blog that demonstrate the potential for creating high-density, human-friendly housing via mobile home parks. Gardner takes a mobile home park in Bradenton, Florida as an example.

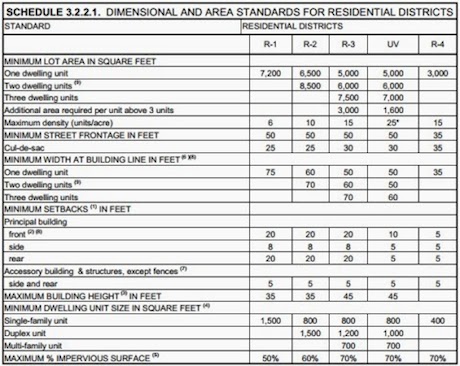

The chart above shows the respective zoning requirements for R-1 (single-family house), R-2 (two-family), R-3 (multi-family), R-4 (mobile home) and UV (Urban Village, a seldom-used designation). Gardner spells out the implications of this nicely:

Note that in the mobile home district, minimum lot sizes are less than half that required in the single-family district, even though both only permit single-family homes! The comparative minimum dwelling sizes are a strikingly divergent 1,500 sq. ft. and 400 sq. ft. The mobile home zone is allowed to be built so densely, in fact, that its maximum permitted units/acre is equivalent to the multifamily zone. Not shown here are the parking tables, which require only one space for mobile homes, yet two for single-family homes, regardless of square footage.

Also worth noting are the respective setback distances. A setback is the required distance from home to its lot’s border, and it’s a prime culprit of creating sprawl. Single family homes require 20′ of setback in both front and back; for mobile homes it’s 5′. The image below shows an aerial view of R-1 and R-4 neighborhoods and illustrates how the minimal setbacks and lot size affect overall density.

Gardner explains that one of the reasons mobile home parks enjoy this type of flexible zoning is their history as a more transient form of housing. Gardner speculates that regulators saw mobile home sites “more as parking lots than as a formal arrangement of streets and building lots,” and thus didn’t impose all of the restrictions they did for site-built, single-family housing.

One hurdle of the mobile home park is architectural. Mobile homes have standard dimensions; single-wides are 18′ (5.5 m) or less in width and 90′ (27 m) or less. R-4 zoning is designed around these dimensions and parks like the one Bradenton are required to use mobile homes rather than site-built housing. Mobile homes are historically poorer quality than site-built housing. This author actually lived in a mobile home for a couple years and the house itself was pretty flimsy in all the ways you would guess. The ability to put site-built or sophisticated mobile home architecture in mobile home parks would be a huge step toward creating sensible, detached, single-family housing.

While mobile home parks are not a panacea for the world’s housing woes, they do present one compelling model for the future, where housing is built sensibly and with community formation in mind. These are both good things. It’s probably about time conventional architecture and zoning starts veering away from constructing figurative castles with their large moats.

Thanks for the tip Tim!

Images and content via Old Urbanist blog